The Scriptum Blog / Writing

The making of an Italian leather bound journal

In a quest for some exciting new lines for this spring, we decided it was time to pay a visit to one of our suppliers to see exactly how their leather bound journals are made. We like to know precisely where our stock comes from, as we want to be able to talk with confidence about every detail of a product’s journey: its materials, its history, its creation. Provenance is important; before becoming part of your story, a journal has a tale of its own.

Amarcord is an Italian bindery based in Piacenza, a beautiful cobbled and campanile-dotted town halfway between Milan and Bologna. The company’s name is a local dialect word for “I remember” in a rather nostalgic sense - very fitting for a maker of journals, the repositories of memories and dreams. We have been working with Amarcord for a number of years, and as well as many of our best-selling journals, they also supply some of our music manuscript journals, wine records and restaurant books, so we were rather excited to meet the craftsmen who make them.

Amarcord is run by third generation leathersmith Sergio, whose grandfather set up the company, originally to make leather luggage and belts, shortly after returning from the second world war. Sergio's father eventually took over the business, and then Sergio in his turn, building on the years of family experience in leatherwork to specialise in journals and binding. He works closely with his colleague Daniela, who is Piacenza born and bred, and passionate about not only Amarcord journals but all the produce and history of their region. When not hard at work in the workshop itself, Sergio and Daniela sit in their office at patchwork leather desks (made in-house, naturally) drinking fragrant espresso and arranging the distribution of their journals all around the world.

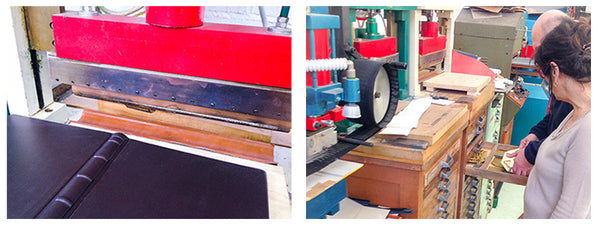

The workshop is a light, airy building a few miles from the city centre, filled with the heavy scent of leather, paper, and glue, and the clatter and whir of machines ticking over, waiting to be used by the small team of leatherworkers. With this artisan style of production, each journal comes under Sergio's watchful eye and allows him to ensure the quality of every piece is up to his standards.

The journal-making process begins with the leather. The leather for our Verona journals comes from the Veneto, where the cow hides are tanned, dyed, and greased to give their distinctive soft suede-like texture. The leather for our Trieste journals and Embossed Window journals with a smoother, shinier finish, comes from nearby Tuscany. Amarcord have dozens of other styles and colours of hides stacked in rolls along one wall of the workshop - it’s difficult to pass by without stroking each one to feel the grain and finish, and nigh on impossible for us to decide which we want to use for our order. After poking, prodding and a good deal of sniffing, we finally pick out our favourites to make up the journals which will arrive in Oxford in the spring.

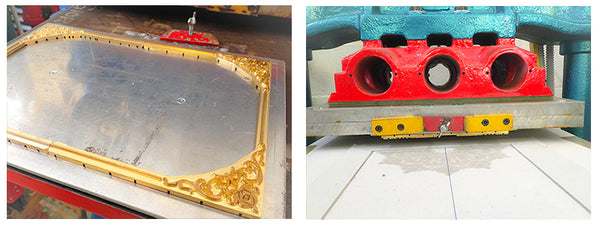

Once we have selected the type of leather, it is taken it to the cutting press. Sergio chooses a sharp-edged press, exactly like an industrial-strength cookie-cutter, for whichever shape of cover he needs, and positions it carefully on top of the hide. The heavy stamp is brought down hydraulically, pushing the sharp edge of the press cleanly through the tough leather to leave the basic shape of the journal, and sometimes a double hole for a tie-closure.

If it is a hardback, the leather now needs to be attached to a thick layer of mount board to give it stiffness and shape. For spines with the traditional ridges, a piece of ridged board is also added to give the leather its characteristic shape after a short stint in a curved spine press. Now comes the embossing. Metal blocking dies with a bewildering array of patterns are neatly filed in drawers, ready to stamp their pattern onto the leather. To do this, the die is positioned in a stamping machine which heats the metal to 125°C before bringing it down on the leather. The heat and the pressure stamp the pattern indelibly onto the leather’s surface.

The next step is the block; a bound collection of pages to put inside the journal. Amarcord use Italian-made book blocks with 85gsm acid-free paper as standard (120gsm for sketch books). The leaves within the block are stitched together as well as glued at the spine, leaving the pages firmly and tightly bound even if the journal is opened completely flat or folded back on itself. Laura Berretti, an expert in traditional Italian marbling techniques, also sends Amarcord blocks with hand-marbled edges from her atelier in Florence. These are the blocks used in our Trieste journals. For books with handmade paper, luxurious deckle-edged Amatruda Amalfi paper is stitched together by hand in the workshop to create the block from scratch.

If the block needs to be resized, or mount board cut, there are a pair of guillotines for the job. One is a modern machine, which you have to press two buttons about a metre apart to operate - the idea is that as you need two hands to bring the guillotine down, you can't accidentally chop off your own fingers by mistake! The other looks more like a medieval decapitation device than an innocent bindery tool; a manually operated, meter-long, razor-sharp blade which comes chopping down with a sinister swish to cleave easily though the thickest mount board.

Once the block has been selected and trimmed to size, it is time to unite it with the cut-out and embossed leather. In a few quick, deft motions, the block is run through a revolving press, a bit like a mangle. This coats it with a fine layer of glue from the roller, which is fed from a bubbling pot of the treacly liquid. The block is snatched from the roller immediately, then aligned with and pressed onto the leather cover by hand, binding the two firmly and evenly together. It is then put in another press for five minutes while the glue dries. While the team at Amarcord make all this look easy, moving with the assurance and dexterity born of long practice, we Scriptonians kept our hands safely tucked in our pockets, imagining accidentally gluing our fingers to that inexorably revolving mangle.

If the journal has any extra features, such as a tie closure, this is the time to add them. A thin leather thong, stamped out of leather by the same process as the journal covers, is looped carefully through the holes; a fiddly process. Then a beechwood bead, sourced from Bergamo (just north of Milan) is threaded on to make a toggle closure, and the ends of the thong neatly tied and snipped.

And finally, the journal is finished! Although we have been working with Amarcord for several years, it was inspiring and somehow humbling to see how much attention to detail, how many years of experience go into producing each and every journal handmade in their workshop. It all comes back to provenance: if you know where something comes from, you can be assured of not only its quality, but the tradition in which its making is rooted. It was fascinating to discover the story behind each part of our journals, and to meet the people whose passion for traditional leatherwork keep us journal-lovers supplied with the objects of our desire. We can’t wait for the new styles we have ordered to arrive!

Thank You Cards and the Dreaded Thank You Loop

We all know that slightly flat feeling when you have spent time, money, and above all, effort on choosing a present which you know is utterly perfect for someone, but you haven't seen them open it. We've all been on the other side too - received a gift which has touched us ("I can't believe she remembered I wanted this!") but have had to restrain our visible enthusiasm lest Auntie Myrtle realise her Twix mug wasn't quite as thrilling as that incredible compass globe from cousin Althea. It's polite to write a thank you card for any present, but the really thoughtful ones truly deserve it. So, whether it's a dutiful note for a gesture gift or a heartfelt thank you for a long-desired treat, here are our four simple rules for the perfect thank you letter:

1. Be prompt. The acceptable length of the note is proportional to the time you've taken to send it. A couple of lines within a week of receiving a present is perfect, while if you leave it longer, you should really write at more length and detail to justify how long it has taken. And let's face it, the longer you leave it, the less likely you are to write it at all.

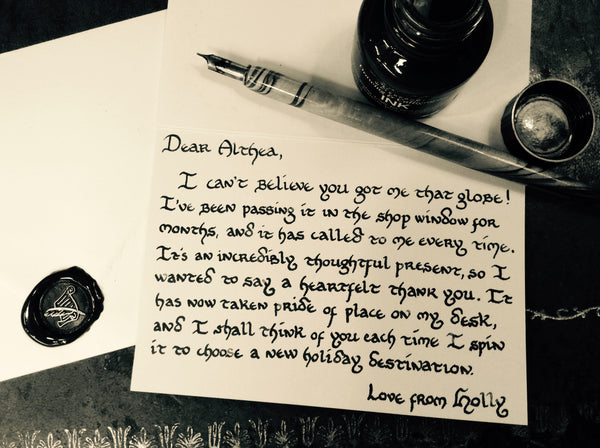

2. Be specific. Saying "thanks for the present" sounds like (and probably means) you can't quite remember exactly what they got you. Telling the giver how you have used/will use the item they got you is a nice way of letting them know you appreciate the qualities of the present.

3. Draft it. A two minute scribbled draft will help avoid repetition of fulsome adjectives ("lovely" sounds a bit disingenuous when it has been used three times in a row) and also prevent spelling mistakes and messy crossings out. It doesn't have to be a masterpiece of world literature, but coherence and elegance are always worth aiming for.

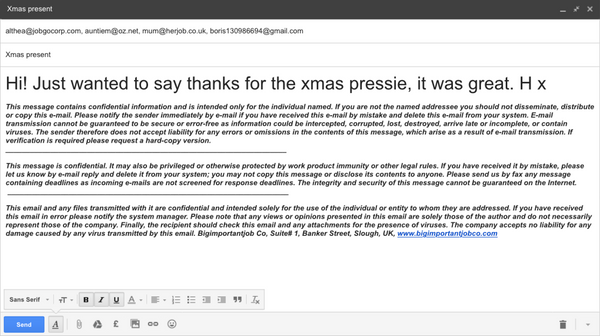

4. Handwrite it. Even though it puts my views at odds with the über arbiter of etiquette, Debretts, who suggest that an emailed thank-you is sometimes acceptable, to me they will always look like you are just filling a dull 5 minutes at work, and frankly aren't worth the cyberspace they're written on. A spontaneous text at the moment of unwrapping is all well and good, but the rarer it becomes to write by hand, the more appreciated proper handwritten thank you cards become.

Some examples...

The dutiful note with draft, written the day after receiving the present:

The sincerely grateful note, written after a week:

The "I don't care about your present or you" email:

A word of caution to end on - never write a thank you card for a thank you card. This kind of gratitude one-upmanship is not only in poor taste, but can lead to the dreaded thank you loop. If you have friends who are also stationery addicts, it is disturbingly easy to become trapped on a Möbius strip of thank you notes, thanking them for thanking you, and receiving thanks for your thanks of their thankfulness.

The dreaded thank you loop

Once entered, the thank you card loop can only end in bankruptcy, madness, or death (or more realistically, repetitive strain injury in your writing hand). Having said that, if you insist on engaging in competitive gratitude, you can break the loop by sending a thank you card so magnificent that no reply is possible... so get these ones, and follow the four thank you card rules. You'll win every time.

Letterpressed Thank You Card Set

Handwriting and expression: what we lose when we forgo the pen

An historian came into the shop this morning to look at our fountain pens, and we started talking. He explained that the reason he writes with a pen is to feel connected to the people whose lives he is examining. He studies the early modern period, and when he looks at documents written by hand, he can see if someone was writing in a rush, in a temper, with passion, or in a lazy relaxed scrawl. The way they write, just as much as what they write, influences his analysis of their meaning. After this conversation, my thoughts (as they often do) turned to handwriting.

It seems disingenuous to complain about this on a blog, but we lose so much when we move our hands from the pen to the keyboard; the reader can't ever see my deleted first choice when I replace a word, can't tell when I've sat for minutes on end searching for a more apt expression, can't see the flow of my thoughts as I shuffle these paragraphs round on the screen. But a pause in handwriting, while the writer sits and considers what to say next, is often subtly marked by a physical trace on the paper; a blot while the pen pauses at the end of the thought or a heavier hand when sad words come unwillingly. There are myriad traces of the writer's progress, from scoring through one choice of word to replace it with something more telling, to the rushed and jagged spurts of inspiration. Have you ever looked at poetry manuscripts? No matter how beautiful and well-chosen the words of the final piece, I find exploring the poet's scribblings and crossings out infinitely more fascinating.

In thoughts that have been typed, qualities such as nuance and irony have to be carefully built into the language itself to avoid being misinterpreted or even missed altogether. This careful consideration of the words we choose might have been a positive consequence of typing if it happened more: but think how often your dashed-off texts and emails are misconstrued by someone who can't gauge their tone, or how often you find yourself flicking to your emoji keyboard as a quick way of ensuring this doesn't happen. To be witty, I should insert a wry-faced emoticon here, but I simply can't bring myself to do it. Our language, or at least our capability of using it to communicate complex thoughts and emotions, becomes worryingly flat when we turn to the keyboard. Little effort is being made to distinguish between subtle gradations of meaning when all you choose is the size of the grin on your smiley.

While content is important, handwriting itself is also undeniably evocative. It is an artefact of time and effort, and this makes the handwritten message, whatever its content, more meaningful than the typed version. I've said it before in these blog posts and I will doubtless say it again; when you receive a handwritten note, your heart leaps in a way it will never do for an email. Leave aside all that 'handwriting experts' proclaim to know about your character from how you form your risers: for me, the simple thrill of recognition is enough. When I see an envelope addressed to me in back-slanted, looping, regular writing, I know immediately it is from my Gran. I read a page of handwritten directions a friend has written, directing me to his unSatNavable house, in a hand so firm and decisive the ink is always scored into the paper, and wish I was always so sure about what I was writing. I receive a thank-you note from an old housemate in his small, neat, almost childish printing, yet it still evokes long-ago messages on the fridge warning of dire consequences for anyone bold or foolish enough to eat his cheese.

Of course when you are late to meet a friend, nothing is better than a quick text to let them know where you are. Of course you won't have to manically pat down all your pockets hunting for your shopping list when it's safe on a smartphone app. Of course when you want a quick answer from a colleague you aren't going to send a masterpiece of calligraphy across the office via carrier pigeon. I don't want this to seem like an anti-technology rant; tear off my parchment mask and you'll find a true technophile underneath. But there is space in the world for the old and the new, for the functional and the beautiful. I wish that the people who come into our shop and say "lovely stuff, what a shame no one writes any more" would take five minutes off Facebook-stalking acquaintances to pick up a pen and dash off a postcard to a friend they hadn't seen in a while, and miss. That rather than "liking" someone's post about the birth of their baby, people would sit down and write to the parents, finding words not only to congratulate the new family but also to share their own experiences of suddenly finding a beloved son, god-daughter, nephew, or grandchild in their lives. Typing is convenient, functional, and necessary. Handwriting is sentimental, emotional, and human. We must not let it be lost.

Victorian nibs and other treasures

A double-headed nib and other beauties unearthed in the quadrennial spring clean of our nib box. A few of these nibs are modern, but we have some dating back to the Victorian era. Writing companies really knew how to advertise their wares back then; one of the oldest boxes of nibs proclaims "3007 newspapers recommend them" along with a charming little rhyme calling their nibs "a boon and a blessing to men"!